During a recent Lions Club dinner I was asked, “What happens if a state cannot pay its bills? Can a state be dissolved?” The questions were prompted by my comments about Detroit’s bond rating downgrade, their ensuing bankruptcy, the bailout of Detroit’s city employee pension plan and South Carolina’s problems with our state retirement system.

Being a lawmaker rather than a lawyer – only a slight difference on the credibility scale – I assured them that I was not issuing a legal opinion. I answered that it was my belief that no other governmental entity can dissolve an individual state whose citizens have voted to join the United States.

States are our first governmental principle – they formed our federal government and they form the local governmental entities within their borders. States retain the original creative power.

No state has ceased to exist in our national history. Through wars, economic disasters and civil unrest, these United States have remained intact with each member state retaining its individual constitution

The same cannot be said for counties and cities – the two primary local governmental entities formed by states. Municipalities are regularly dissolved after their populations decrease to the point that their tax base cannot pay for basic municipal services. Driven by economic downturns or poor governance, counties and cities declare bankruptcy more than most people realize and at great cost to their creditors and taxpayers.

To get an idea of the cost, Forbes reports that the five largest city and county bankruptcies since 1990 are Detroit (2013, $18 billion), Stockton (2012, $1 billion), San Bernardino County, CA (2012, $500 million), Jefferson County, AL (2011, $4 billion), and Orange County, CA (1994, $2 billion).

Being the most recent, Detroit offers a fresh example. The city was poorly managed for decades. By 2013, large numbers of residents had fled, leaving the streets to resemble a ravaged city abandoned after a siege. City government was $18 billion in the hole. The city employee pension fund siphoned off 40% of Detroit’s general fund every year just to stay solvent. After their bond rating was downgraded to “junk” status, the city filed for bankruptcy. Their creditors were shook down for $7 billion during the bankruptcy negotiations and Motown was saved for the time being.

Now here’s where the two paths diverge in a red ink stained wood. Cities and counties may declare bankruptcy if their state constitutions allow it; states cannot declare bankruptcy.

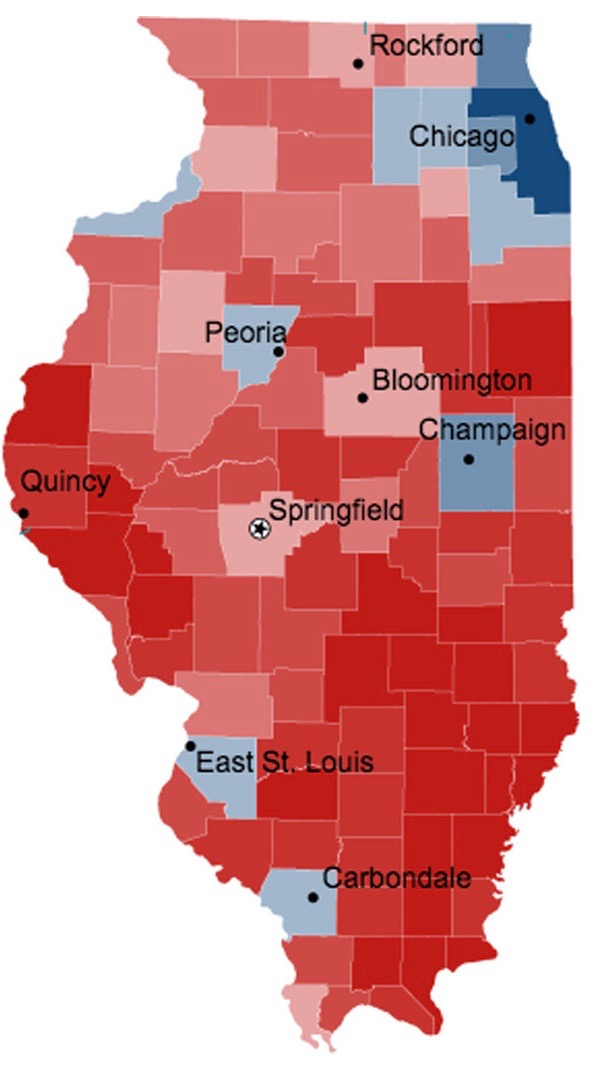

Sometime this month, Standard & Poor’s will determine if Illinois bond rating should drop to “junk” status. If dropped, a driving factor in their decision will be the state’s unfunded pension obligation of $251 billion to the Illinois state retirement system.

The Illinois legislature tried to dodge this massive liability by passing a pension reform bill in 1995. That bill required the retirement system to be 90% funded in 50 years. Instead of improving the funding status of the plan, it codified the underfunded status indefinitely.

The bill’s reform measures might have worked if the Illinois legislature had created a sustainable revenue flow into the pension system that ensured its viability. To do so would have required a cut to the state budget or a tax increase combined with a large dose of political courage. That didn’t happen.

In addition to the $251 billion pension debt, Illinois has $15 billion in unpaid bills, their lottery commission does not have enough funds to pay the winners and their legislature has not passed a budget in three years.

Illinois has limited options. The state can default on their bonds but will be sued by the bondholders. They cannot default on their state pension obligation. The Illinois constitution bars their legislature from reducing pension payments. The likelihood of a federal bailout of a state pension system is nonexistent even if it were constitutional. If Illinois bond rating falls to “junk” status, the interest cost that they pay on each bond it issues will increase. That increase is a direct hit against the Illinois taxpayer.

South Carolina should check a mirror to make sure Illinois isn’t staring back at us. Both states made the top ten list for most underfunded state pension plans. Both states passed pension reform bills with targeted debt reductions. Illinois failed to fund a dedicated revenue stream to decrease their pension debt.

The South Carolina legislature has a joint committee studying on the recipe for a sustainable revenue stream for our pension system. We shouldn’t forget that a dash of political courage will be the most necessary ingredient.